Magicians, psychics and other sparkly frauds have been scamming the gullible and dim-witted for centuries using elaborate trickery to simulate fantastic powers. But now science is finally here, and it's going to follow through on all of their broken promises.

Here are the technologies that, if you could take them back in time, would totally let you cash in as a wizard.

The Scam:

In many ways, mind reading is a lot like the human digestive system: no matter what you put into it, ultimately all you're getting out is a bunch of shit. Psychics are mostly just using cold readings and leading questions to pick up clues. They see a guy in a red, white and blue cowboy hat and the "spirits" tell them that he likes country music. The guy is impressed, and hands them money to hear more.

"I'm sensing an object."

"It's not an object."

"Of course! I'm sensing something like an object, a... person!"

"My god! It is a person! My wife, Jenny!"

"Aha! Women are basically objects; you see how the reading was murky."

By creatively hedging their guesses and keeping all information vague, a good cold reader can emulate psychic abilities at least well enough to fool chumps, and chumps' money spends like anybody else's.

How it's Becoming Real:

We bet airport security would love to have one of these that you pass through, flashing your thoughts up on a screen for some bored TSA agent to chuckle at. We've got a feeling that in 20 years there'll be a booming industry in telepathy-blocking skull implants.

The Scam:

Telekinesis is the ability to move or interact with physical objects using only one's thoughts, and charlatans have been replicating it for centuries. Like say you want to bend a spoon with your mind. Simply misdirect the audience while you use your hands to bend the spoon in such a way that, when viewed from a top down angle, it still appears to be unbent. As you slowly adjust that viewing angle, the spoon appears to bend before the audience's very eyes! Hey! Look at you! You're better than Criss Angel!

Oh, not "better" in terms of magic tricks; he's got some pretty neat ones. You're just better than him in general. Because you're not Criss Angel. It's uh... it's not a hard thing to do.

How it's Becoming Real:

About five years ago, a group of scientists successfully decoded the brain signals human beings use to control their hands. Because said scientists were both astoundingly awesome and amazingly irresponsible, they then used this discovery to implant microchips in the brains of monkeys which allowed them to move computer cursors with their brain.

Guys, we need to sit you down and show you a little movie called The Lawnmower Man.

Fast forward a few years and now we're starting to see the first wave of products resulting from that experiment. Behold the BrainGate, and despair!

From the company Cyberkinetics--which totally does NOT sound like a villainous organization dedicated to mass producing psychic robots--the BrainGate is a chip implanted in your motor cortex that monitors your brain activity and converts it into computer commands used to operate machinery. It was originally built for amputees and paraplegics, but the company has recently received a $4.25 million grant from the Department of Defense for their product.

It's not clear exactly what they're going to do with the technology, but odds are it's going to be less along the lines of "helping paraplegic monkeys to live better lives" than it will be "fusing human brains into unstoppable, unkillable robot bodies." Hello? RoboCop 2? Seriously, do you guys not have Cinemax?

The Scam:

Alchemy is the ancient, bullshit version of chemistry. When most people hear the word they immediately think of the alchemists who claimed they could turn lead into gold (a practice called Chrysopoeia, which is not to be confused with Chrysopelea, which is a flying snake. Seriously, don't confuse them. Your experiments will get terrifying in a hurry.)

Of course, the closest old-timey alchemists ever really got was mixing sulfur and gold powder into a metal to turn it yellow. That's right: All it took to create "gold" from lead was to put some gold in it! Good god, it was staring us in the face the entire time!

How it's Becoming Real:

Science has made monumental leaps since that era when alchemy was considered the second-most promising method of obtaining gold after "capturing a leprechaun." We now know that gold is an element that simply has three fewer protons than lead. If you could somehow change that using SCIENCE...

Oh, actually we're kind of late on this one. Back in 1980, a scientist named Glenn Seaborg accidentally made gold out of bismuth, using the aforementioned proton-plucking method (OK, it was a bit more complicated than that).

Yes, bismuth, the same stuff that's in Pepto Bismol.

It was only a few thousand atoms' worth, and the cost of doing it was way more than the resulting gold would be worth. But still. He made gold.

And mankind is really just getting started with the whole "change elements by farting around with their protons" business. Transmutation of elements is one of the things they're always doing at CERN, home of the Large Hadron Collider. Though they're talking less about turning lead into gold and more about turning radioactive waste into something that won't poison our great great grandchildren.

But hey, thanks to Cracked, Google search and poor reading comprehension, we're laying odds that at least one Internet-frequenter will be microwaving some Pepto tonight, and keeping that old dipshit alchemist spirit alive!

The Scam:

Chiromancy, or "palm reading" is the supposed ability to discern a person's dominant personality traits or even divine their future by interpreting the lines on their palm. It's basically just a hand-fetish version of the cold reading we discussed earlier: close inspection of the hands can say a lot. The placement and amount of calluses, how well the nails are kept, indents from rings--they're all general clues to a person's life.

How it's Becoming Real:

Your hand really is a gold-mine of information about your genetics and overall health. We have previously explained how researchers have figured out that finger length can determine sexual behavior, a.k.a. the Digit Ratio Theory.

But your fingerprints also contain a load of information about certain genetic disorders. For example, if you have something called Ulnar Swirls (pictured below) it's likely you have Down's syndrome.

The same creases in the palms the fortune tellers claim to read are actually indicators of certain genetic disorders and even fetal alcohol syndrome.

Of course, old-fashioned palm readers have seized on this to claim they were right all along. See! If scientists can find genetic clues in your Life Line, surely our experts will be able to predict when you'll meet your soulmate! For a small fee!

The Scam:

This is the big one. Whether it's a lady with a crystal ball, a cult leader predicting apocalypse or Sylvia Freaking Browne, there has always been a thriving industry in making (often vague) predictions about the future. You can be wrong 99 times out of a hundred, but as long as you get one guess right (usually something like, "I predict a major disaster somewhere in Asia this year") your followers will forget all the misses.

Just ask Ms. Browne, who has turned a career of never successfully predicting anything into a business that charges $850 dollars for a telephone reading.

How it's Becoming Real:

It looks like the only thing between us and having the computer equivalent of a crystal ball is getting the software right--and trust us, they're working around the clock.

Two ongoing crises are driving the research right now: Global Warming, with the corresponding need to develop more accurate models to predict warming trends, and the recent financial collapse that managed to blindside every expert whose job it is to see shit like that coming. Strangely, in the future the same techniques may be used to predict both.

It's not easy; it takes a shitload of computing power, and massive amounts of past and current data for a piece of software to predict what's going to happen. But, for instance, one model already predicted a crash of the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The programmers aren't claiming magic, the software just recognized that buyers tend to behave a certain way before a steep drop.

Meanwhile the U.S. Department of Defense is using computer models right now to predict geopolitical outcomes, anticipating events like regime changes using number-crunching techniques probably not all that different from what statistician, Nate Silver, uses to nail down his creepily accurate election forecasts.

And if you can get rough-yet-fairly accurate predictions with just some dudes and their desktop PC's, you can only imagine what could happen if we had, say, a gigantic supercomputer on the task. Or instead of imagining it, we could just go to Los Alamos National Laboratories where they have this fucker:

That's the Roadrunner system, it operates at 1.6 PetaFLOPS (that is, one point six quadrillion or 1,600,000,000,000,000 calculations a second) and they're busily teaching it to predict things. They're running mathematical models that will let it map everything from the chaotic spread of a wildfire to the expansion of the universe.

Of course, even then, the models are simply predicting broad trends. They could maybe predict what the crime rate in Baltimore will be next year, but can't predict that the guy in the next cubicle over is about to stab some dudes. No, for that you'd need the FAST (Future Attribute Screening Technologies) program, a system developed by the Department of Homeland Security that can measure your vital signs and fleeting facial expressions and accurately predict that you're going to commit a crime in the near future.

All of which leaves us with one question: What happens when personal computers get powerful enough to run the prediction software on their own, and everyone has access to it? How will people's behavior change when they know what the computer is predicting they'll do? And how will the computers adjust their predictions based on the subjects of their predictions knowing the predictions? Or will it have predicted the subjects' awareness of the predictions as part of its original predictions?

Wait, this is why they started burning witches, isn't it?

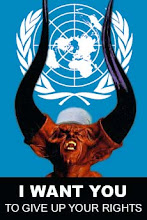

Pentagon used psychological operation on US public, documents show

Wednesday, October 21st, 2009 -- 10:12 am

Figure in Bush propaganda operation remains Pentagon spokesman

In Part I of this series, Raw Story revealed that Bryan Whitman, the current deputy assistant secretary of defense for media operations, was an active senior participant in a Bush administration covert Pentagon program that used retired military analysts to generate positive wartime news coverage.

A months-long review of documents and interviews with Pentagon personnel has revealed that the Bush Administration's military analyst program -- aimed at selling the Iraq war to the American people -- operated through a secretive collaboration between the Defense Department's press and community relations offices.

Raw Story has also uncovered evidence that directly ties the activities undertaken in the military analyst program to an official US military document’s definition of psychological operations -- propaganda that is only supposed to be directed toward foreign audiences.

The investigation of Pentagon documents and interviews with Defense Department officials and experts in public relations found that the decision to fold the military analyst program into community relations and portray it as “outreach” served to obscure the intent of the project as well as that office’s partnership with the press office. It also helped shield its senior supervisor, Bryan Whitman, assistant secretary of defense for media operations, whose role was unknown when the original story of the analyst program broke.

In a nearly hour-long phone interview, Whitman asserted that since the program was not run from his office, he was neither involved nor culpable. Exposure of the collaboration between the Pentagon press and community relations offices on this program, however, as well as an effort to characterize it as a mere community outreach project, belie Whitman’s claim that he bears no responsibility for the program’s activities.

These new revelations come in addition to the evidence of Whitman’s active and extensive participation in the program, as Raw Story documented in part one of this series. Whitman remains a spokesman for the Pentagon today.

Whitman said he stood by an earlier statement in which he averred “the intent and purpose of the [program] is nothing other than an earnest attempt to inform the American public.”

In the interview, Whitman sought to portray his role as peripheral, noting that his position naturally demands he speak on a number of subjects in which he isn’t necessarily directly involved.

The record, however, suggests otherwise.

In a January 2005 memorandum to active members of both offices from then-Pentagon press office director, Navy Captain Roxie Merritt – who now leads the community relations office -- she emphasized the necessary “synergy of outreach shop and media ops working together” on the military analyst program. [p. 18-19]

Merritt recommended that both the press and community relations offices develop a “hot list” of analysts who could dependably “carry our water” and provide them with ultra-exclusive access that would compel the networks to “weed out the less reliably friendly analysts” on their own.

“Media ops and outreach can work on a plan to maximize use of the analysts and figure out a system by which we keep our most reliably friendly analysts plugged in on everything from crisis response to future plans,” Merritt remarked. “As evidenced by this analyst trip to Iraq, the synergy of outreach shop and media ops working together on these types of projects is enormous and effective. Will continue to examine ways to improve processes.”

In response, Lawrence Di Rita, then Pentagon public affairs chief, agreed. He told Merritt and both offices in an email, “I guess I thought we already were doing a lot of this.”

Several names on the memo are redacted. Those who are visible read like a who’s who of the Pentagon press and community relations offices: Whitman, Merritt, her deputy press office director Gary Keck (both of whom reported directly to Whitman) and two Bush political appointees, Dallas Lawrence and Allison Barber, then respectively director and head of community relations.

Merritt became director of the office, and its de facto chief until the appointment of a new deputy assistant secretary of defense, after the departures of Barber and Lawrence, the ostensible leaders of the military analyst program. She remains at the Defense Department today.

When reached through email, Merritt attempted to explain the function of her office's outreach program and what distinguishes it from press office activities.

“Essentially,” Merritt summarized, “we provide another avenue of communications for citizens and organizations wanting to communicate directly with DoD.”

Asked to clarify, she said that outreach’s purpose is to educate the public in a one-to-one manner about the Defense Department and military’s structure, history and operations. She also noted her office "does not handle [the] news media unless they have a specific question about one of our programs."

Merritt eventually admitted that it is not a function of the outreach program to provide either information or talking points to individuals or a group of individuals -- such as the retired military analysts -- with the intention that those recipients use them to directly engage with traditional news media and influence news coverage.

Asked directly if her office provides talking points for this purpose, she replied, “No. The talking points are developed for use by DoD personnel.”

Experts in public relations and propaganda say Raw Story's findings reveal the program itself was "unwise" and "inherently deceptive." One expressed surprise that one of the program's senior figures was still speaking for the Pentagon.

“Running the military analyst program from a community relations office is both surprising and unwise,” said Nicholas Cull, a professor of public diplomacy at USC’s Annenberg School and an expert on propaganda. “It is surprising because this is not what that office should be doing [and] unwise because the element of subterfuge is always a lightening rod for public criticism.”

Diane Farsetta, a senior researcher at the Center for Media and Democracy, which monitors publics relations and media manipulation, said calling the program “outreach” was “very calculatedly misleading” and another example of how the project was “inherently deceptive.”

“This has been their talking point in general on the Pentagon pundit program,” Farsetta explained. “You know, ‘We’re all just making sure that we’re sharing information.’”

Farsetta also said that it’s “pretty stunning” that no one, including Whitman, has been willing to take any responsibility for the program and that the Pentagon Inspector General’s office and Congress have yet to hold anyone accountable.

“It’s hard to think of a more blatant example of propaganda than this program,” Farsetta said.

Cull said the revelations are “just one more indication that the entire apparatus of the US government’s strategic communications -- civilian and military, at home and abroad -- is in dire need of review and repair.”

A PSYOPS Program Directed at American Public

When the military analyst program was first revealed by The New York Times in 2008, retired US Army Col. Ken Allard described it as “PSYOPS on steroids.”

It turns out this was far from a casual reference. Raw Story has discovered new evidence that directly exposes this stealth media project and the activities of its participants as matching the US government’s own definition of psychological operations, or PSYOPS.

The US Army Civil Affairs & Psychological Operations Command fact sheet, which states that PSYOPS should be directed “to foreign audiences” only, includes the following description:

“Used during peacetime, contingencies and declared war, these activities are not forms of force, but are force multipliers that use nonviolent means in often violent environments.”

Pentagon public affairs officials referred to the military analysts as “message force multipliers” in documented communications.

A prime example is a May 2006 memorandum from then community relations chief Allison Barber in which she proposes sending the military analysts on another trip to Iraq:

“Based on past trips, I would suggest limiting the group to 10 analysts, those with the greatest ability to serve as message force multipliers.”

Nicholas Cull, who also directs the public diplomacy master’s program at USC and has written extensively on propaganda and media history, found the Pentagon public affairs officials’ use of such terms both incriminating and reckless.

“[Their] use of psyop terminology is an ‘own goal,’” Cull explained in an email, “as it speaks directly to the American public’s underlying fear of being brainwashed by its own government.”

This new evidence provides further perspective on an incident cited by the Times.

Pentagon records show that the day after 14 marines died in Iraq on August 3, 2005, James T. Conway, then director of operations for the Joint Chiefs, instructed military analysts during a briefing to work to prevent the incident from weakening public support for the war. Conway reminded the military analysts assembled, “The strategic target remains our population.” [p. 102]

Same Strategy, Different Program

Bryan Whitman was also involved in a different Pentagon public affairs project during the lead-up to the war in Iraq: embedding reporters.

The embed and military analyst programs shared the same underlying strategy of “information dominance,” the same objective of selling Bush administration war policies by generating favorable news coverage and were directed at the same target -- the American public.

Torie Clarke, the first Pentagon public affairs chief, is often credited for conceiving both programs. But Clarke and Whitman have openly acknowledged his deep involvement in the embed project.

Clarke declined to be interviewed for this article.

Whitman said he was “heavily involved in the process” of the embed program's development, implementation and supervision.

Before embedding, reporters and media organizations were forced to sign a contract whose ground rules included allowing military officials to review articles for release, traveling with military personnel escorts at all times or remaining in designated areas, only conducting on-the-record interviews, and agreeing that the government may terminate the contract “at any time and for any reason.”

In May 2002, with planning for a possible invasion of Iraq already in progress, Clarke appointed Whitman to head all Pentagon media operations. Prior to that, he had served since 1995 in the Pentagon press office, both as deputy director for press operations and as a public affairs specialist.

The timing of Whitman’s appointment coincided with the development stages of the embed and military analyst programs. He was the ideal candidate for both projects.

Whitman had a military background, having served in combat as a Special Forces commander and as an Army public affairs officer with years of experience in messaging from the Pentagon. He also had experience in briefing and prepping civilian and military personnel.

Whitman's background provided him with a facility and familiarity in navigating military and civilian channels. With these tools in hand, he was able to create dialogue between the two and expedite action in a sprawling and sometimes contentious bureaucracy.

Buried in an obscure April 2008 online New York Times Q&A with readers, reporter David Barstow disclosed:

“As Lawrence Di Rita, a former senior Pentagon official told me, they viewed [the military analyst program] as the ‘mirror image’ of the Pentagon program for embedding reporters with units in the field. In this case, the military analysts were in effect ‘embedded’ with the senior leadership through a steady mix of private briefings, trips and talking points.”

Di Rita denied the conversation had occurred in a telephone interview.

“I don’t doubt that’s what he heard, but that’s not what I said,” Di Rita asserted.

Whitman said he'd never heard Di Rita make any such comparison between the programs.

Barstow, however, said he stood behind the veracity of the quote and the conversation he attributed to Di Rita.

Di Rita, who succeeded Clarke, also declined to answer any questions related to Whitman’s involvement in the military analyst program, including whether he had been involved in its creation.

Clarke and Whitman have both discussed information dominance and its role in the embed program.

In her 2006 book Lipstick on a Pig, Clarke revealed that “most importantly, embedding was a military strategy in addition to a public affairs one” (p. 62) and that the program’s strategy was “simple: information dominance” (p. 187). To achieve it, she explained, there was a need to circumvent the traditional news media “filter” where journalists act as “intermediaries.”

The goal, just as with the military analyst program, was not to spin a story but to control the narrative altogether.

At the 2003 Military-Media conference in Chicago, Whitman told the audience, “We wanted to take the offensive to achieve information dominance” because “information was going to play a major role in combat operations.” [pdf link p. 2] One of the other program’s objectives, he said, was “to build and maintain support for U.S. policy.” [pdf link, p. 16 – quote sourced in 2005 recap of 2003 mil-media conference]

At the March 2004 “Media at War” conference at UC Berkeley, Lt. Col. Rick Long, former head of media relations for the US Marine Corps, offered a candid view of the Pentagon’s engagement in “information warfare” during the Bush administration.

“Our job is to win, quite frankly,” said Long. “The reason why we wanted to embed so many media was we wanted to dominate the information environment. We wanted to beat any kind of propaganda or disinformation at its own game.”

“Overall,” he told the audience, “we’re happy with the outcome.”

The Appearance of Transparency

On a national radio program just before the invasion of Iraq, Whitman claimed that embedded reporters would have a firsthand perspective of “the good, the bad and the ugly.”

But veteran foreign correspondent Reese Erlich told Raw Story that the embed program was “a stroke of genius by the Bush administration” because it gave the appearance of transparency while “in reality, they were manipulating the news.”

In a phone interview, Erlich, who is currently covering the war in Afghanistan as a “unilateral” (which allows reporters to move around more freely without the restrictions of embed guidelines), also pointed out the psychological and practical influence the program has on reporters.

“You’re traveling with a particular group of soldiers,” he explained. “Your life literally depends on them. And you see only the firefights or slog that they’re involved in. So you’re not going to get anything close to balanced reporting.”

At the August 2003 Military-Media conference in Chicago, Jonathan Landay, who covered the initial stages of the war for Knight Ridder Newspapers, said that being a unilateral “gave me the flexibility to do my job.” [pdf link p. 2]

He added, “Donald Rumsfeld told the American people that what happened in northern Iraq after [the invasion] was a little ‘untidiness.’ What I saw, and what I reported, was a tsunami of murder, looting, arson and ethnic cleansing.”

Paul Workman, a journalist with over thirty years at CBC News, including foreign correspondent reporting on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, wrote of the program in April 2003, “It is a brilliant, persuasive conspiracy to control the images and the messages coming out of the battlefield and they've succeeded colossally.”

Erlich said he thought most mainstream US reporters have been unwilling to candidly discuss the program because they “weren’t interested in losing their jobs by revealing what they really thought about the embed process.”

Now embedded with troops in Afghanistan for McClatchy, Landay told Raw Story it’s not that reporters shouldn’t be embedded with troops at all, but that it should be only one facet of every news outlet’s war coverage.

Embedding, he said, offers a “soda-straw view of events.” This isn't necessarily negative “as long as a news outlet has a number of embeds and unilaterals whose pictures can be combined” with civilian perspectives available from international TV outlets such as Reuters TV, AP TV, and al Jazeera, he said.

Landay placed more blame on US network news outlets than on the embed program itself for failing to show a more balanced and accurate picture.

But when asked if the Pentagon and the designers of the embed program counted as part of their embedding strategy on the dismal track record of US network news outlets when it came to including international TV footage from civilian perspectives, he replied, “I will not second guess the Pentagon’s motives.”

No comments:

Post a Comment