June 25 (Bloomberg) -- In May 2003, President George W. Bush announced that two trailers found in Iraq were biological- weapons labs. His statement contradicted the conclusions reached by a fact-finding group from the Defense Department days earlier. But that report was secret. When it finally surfaced, in April 2006, the U.S. was still mired in a dubious war.

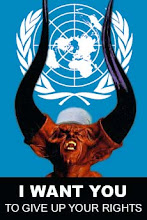

A huge amount of government information is kept from Americans, and Ted Gup argues in his indignant, deeply reported ``Nation of Secrets'' that this state of affairs does our country far more harm than good. Democracy is marked by the free play of conflicting ideas and the accountability of officials to the public; secrecy erodes both.

``A government that has carte blanche to create secrets will constantly be tempted to use secrecy to smother controversy and conceal its own failings,'' he writes. While most Americans now know that Bush hid some of the truth about Iraq, secrecy both in and out of government has mushroomed. And Bush doesn't bear the blame alone.

``Nation of Secrets'' is informed by prodigious reading and hundreds of interviews and crammed with anecdotes, statistics and expert opinion. It burns with the moral ardor that arises from a sense of crisis.

While American diplomats and military leaders have long kept many of their actions secret, this confidentiality has been spreading -- some courts are even hiding the existence of lawsuits.

14 Million Documents

At the Defense Department alone, more than 1,000 officials can classify information. More than 14 million Pentagon papers are classified, but ``almost no one in government believes that anywhere near that number of secrets actually meet the critical standards to be a bona fide secret.'' Instead, as a former top overseer of Pentagon secrecy observes, as a rule ``the higher the classification, the less useful'' the information.

While Gup concedes that of course some secrecy is always necessary, he argues that too little openness makes the country more vulnerable -- for example, when rival agencies keep their knowledge from each other or the president withholds information even from congressional leaders.

A more fundamental threat is to free society itself. When government officials hide information, they gain more leeway to do whatever they want. ``A government free from fears of being contradicted by facts,'' Gup writes, ``becomes emboldened to take liberties with the truth.''

Character Assassination

With impressive sweep, he also turns his gaze elsewhere, deploring the culture of secrecy at colleges, businesses and, not least, the press, implicitly asking how Americans can shine a light on the public sector when we've grown accustomed to being in the dark everywhere else.

Journalists can use unverified information from secret sources to assassinate character. Even when their motives are purer than, say, Joe McCarthy's, the result can be much the same.

Consider the ``terrifying alliance between the government and the press'' in smearing Wen Ho Lee, the Los Alamos National Laboratory scientist imprisoned in 1999 on suspicion of spying. Of the 59 charges against him, 58 were dropped. (He finally pleaded guilty to downloading defense information on an unsecured computer.)

``One of the great spy stories of the modern era,'' Gup writes, ``was of no more substance than a soap bubble.''

``Nation of Secrets: The Threat to Democracy and the American Way of Life'' is published by Doubleday (322 pages, $24.95).

(Jeffrey Tannenbaum is an editor at Bloomberg News in New York. The opinions expressed are his own.)

To contact the writer of this story: Jeffrey Tannenbaum in New York at jtannenbaum@bloomberg.net .

===============================================================

No comments:

Post a Comment